TECH

New 3D-printing and manufacturing techniques grant more control over energetic material behavior

Much like baking the perfect cake involves following a list of ingredients and instructions, manufacturing energetic materials—explosives, pyrotechnics and propellants—requires precise formulations, conditions and procedures to ensure they are safe and perform as intended.

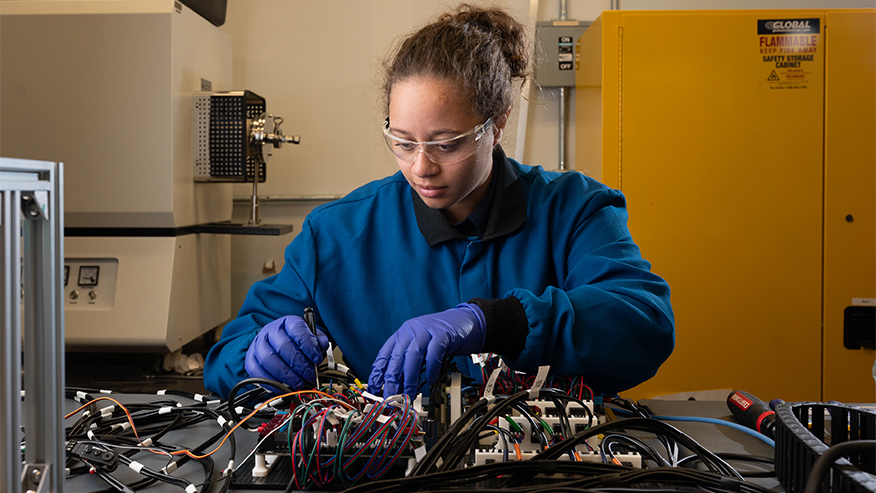

Because any small tweaks or environmental changes can dramatically alter how energetic materials function, Purdue University engineer Monique McClain is developing state-of-the-art tools and methods to control these materials' behavior throughout the manufacturing process and down to the particle level.

McClain, a Purdue assistant professor of mechanical engineering, specializes in the "upstream" or earlier manufacturing stages, such as selecting binders with unique properties to hold energetic particles together and determining how they are mixed to create the final formulation. She focuses on how manufacturing alters the structure and mechanical properties of an energetic material and, in turn, how those changes affect performance and sensitivity.

"An energetic material's manufacturing history, from beginning to end, strongly determines how it behaves during combustion or detonation," McClain said. "We want to ensure that each step is catered toward the material and its intended use so that we're getting a final product that functions in the way we expect."

Much of McClain's body of work focuses on additive manufacturing or 3D printing of energetics. Traditionally, energetic materials have been manufactured using processes such as casting or milling, which prioritize efficiency and scalability. But while these methods are ideal for large batch production, customization is difficult, thereby limiting innovation and compromising on optimal performance.

Additive manufacturing, on the other hand, gives researchers the freedom to experiment with complex geometries and tune specific properties such as burn rate and blast shape.

For instance, McClain and her research team design intentional defects—referred to as pores—to either increase or decrease the likelihood of ignition when materials are subjected to various conditions such as friction, impact or extreme temperatures. Additive manufacturing makes this possible because researchers can customize a 3D printer's nozzles and program it to print specific shapes and patterns.

"Pores and defects are often inevitable, but we can control how and where they show up," McClain said. "When we focus on the microstructure of these materials, we can deliberately select particle sizes or compaction schemes to produce preferred pore distributions that enable the behaviors that we want to see."

Additive manufacturing also makes it easier to experiment with multiple types of materials. In addition to her work with pores, McClain explores how energetic particles adhere to various binders through the 3D-printing process and how to print propellant materials made of multiple materials with disparate characteristics.

Profilometry of PVDF thermoplastic layers. Credit: npj Advanced Manufacturing (2025)In a study published last spring in npj Advanced Manufacturing, McClain and her team looked at adhesion between two polymers with different mechanical properties—a stiff thermoplastic and a soft elastomer—that have been combined into one structure. They found that the 3D-printed surface texture and type of thermoplastic greatly affected how well the two materials blended and held together.

"This study provides a framework and method for studying adhesion of dissimilar materials. This is important because no such guide—and, in turn, little data—on this topic previously existed," McClain said. "The ability to print energetics made of multiple materials gives us even more options for controlling behavior and improving safety."

Although 3D printing is a major part of McClain's work, she also explores how to improve more traditional manufacturing methods.

McClain developed a patent-pending method for manufacturing a polymer-bonded explosive (PBX) molding powder that saves time, eliminates potential hazards and reduces manufacturing waste. McClain disclosed this technology to the Purdue Innovates Office of Technology Commercialization, which has been applied for a patent through the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to protect the intellectual property.

No comments:

Post a Comment