TECH

What is causing the RAM shortage? Chip and supply chain experts explain

Pay any attention to the computer market these days and one thing becomes abundantly clear: RAM—or Random-Access Memory—has gotten pretty expensive. Memory prices have already surged approximately 90% in the first quarter of 2026 compared to the fourth quarter of 2025, according to research firm Counterpoint Technology Market Research.

This change largely stems from a change of focus by Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron, the three biggest RAM component makers in the world, comprising up to 93% of the market.

To accommodate the high computing demands of AI data centers, these companies have accelerated the production of high-bandwidth and high-capacity RAM to supply these centers, according to a market analysis report from the International Data Corporation, or IDC, a US-based market research intelligence firm.

As a result, "this has restricted the supply of general-purpose memory modules and driven up prices across the board," reads a summary of the report.

Matteo Rinaldi, a professor of electrical and computer engineering and the director of Northeastern University's Institute for NanoSystems Innovation, said this shortage is different in nature than the chip shortages the markets experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

"This is more structural," he said. "This is really an AI-driven memory demand shock."

RAM can be understood as a computer's short-term memory center, and it's essential in allowing for multiple applications to be run at once on a computing device. It is a foundational component of any modern computing device—from the cellphone in your pocket to your car's infotainment system.

But an AI data center requires significantly more high-performing memory than a typical consumer electronic device.

"Just to give you an idea, a single AI server can use as much advanced memory as a dozen or even hundreds of traditional laptops," he said. So when hyperscalers, known as massive cloud computing providers, build thousands or tens of thousands of these systems at once, they basically absorb a large fraction of global memory production, Rinaldi added.

RAM memory production is an extremely consolidated business, with the few global players making the majority of these components. For years, these companies have optimized their production cycles for steady consumer demand.

AI, however, has thrown a wrench in the equation, with major players in AI development now requiring extremely powerful components capable of processing massive amounts of data.

"What this really reveals is that modern AI workloads move an enormous amount of data continually," Rinaldi said. "Computing is becoming limited not so much by processors but by my memory bandwidth and data management."

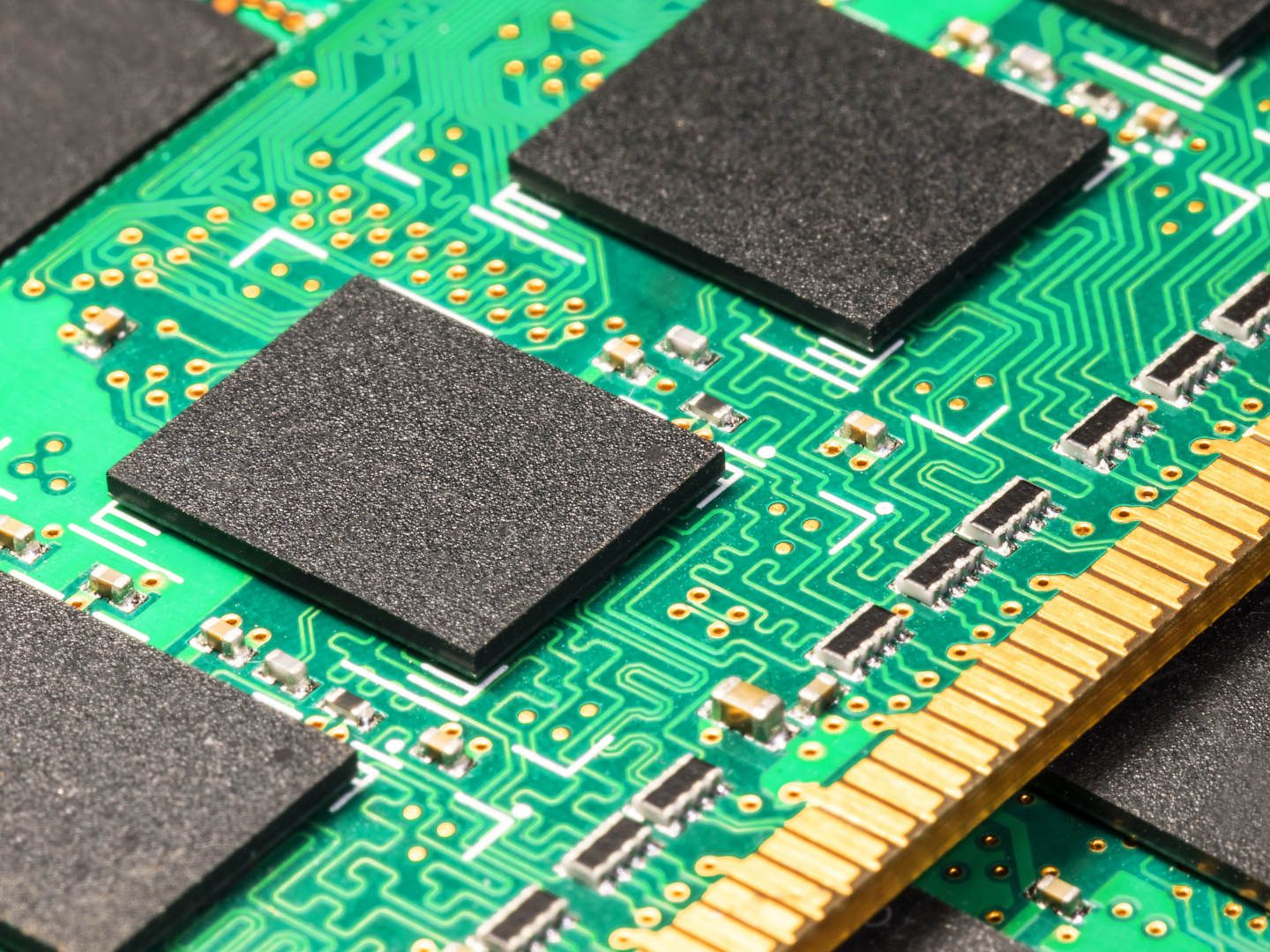

Here’s what you need to know about the global RAM shortage. Credit: Modoono/Northeastern UniversitySo what will the result of this disruption mean for consumers? Higher prices mostly, at least in the medium term, he said.

But it's not just hobbyist PC builders and gamers looking to upgrade their setups who are feeling the impact of this shortage. Nearly everyone planning to purchase a smartphone, desktop computer, laptop, or any computing device in the next few years will likely be impacted.

"Memory is a foundational component of almost every modern electrical system," the electrical and computer engineering expert said, noting that these days even consumer-grade devices are requiring more and more RAM to accommodate new AI features, camera upgrades and other state-of-the-art technologies.

Nada Sanders, a professor of supply chain management at Northeastern University, said this situation highlights exactly where the tech industry's priorities lie. If RAM memory could be considered fuel, in this scenario, the majority of the fuel is being consumed by large corporations operating AI data centers while consumers are left out in the cold, she explained.

"It's a story of the haves and have nots," she said.

Her advice to the average consumer? If you need to make a purchase of a new laptop or cell phone, it will probably be better to buy sooner than later.

"I would be buying new devices now because they are just going to get more expensive, and they are going to continue getting more expensive until this problem is addressed," Sanders said.

It will likely be years before the shortage truly ends because new fabrication facilities need to be built and operational to meet RAM production demands. Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan has publicly acknowledged that there will likely be "no relief until 2028."

"It will ease gradually as both manufacturing and computing architectures evolve," Rinaldi said. "Memory manufacturing expands very slowly because new fabrication plants cost tens of billions of dollars and take several years to build and ramp up."

Provided by Northeastern University

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2026/H/s/ZXoIEhRAi9QoaSok5BUA/5452290-block-lockup-reverse-black-500x500.gif)